Modern point-and-click programming software has replaced the old solder-and-hope method of designing capacitive sensing interfaces.

In recent years, there has been a substantial increase in the use of capacitive sensing interfaces for human input controls in a wide range of applications, from mobile handsets to computers, point-of-service terminals to home electronics, and medical devices to industrial controls. This article will explore the evolution of capacitive sensing design methodologies and outline modern tuning processes that move beyond the guess-and-solder approach, enabling developers to calibrate sensors visually in real-time with no coding involved.

Capacitive sensing is a form of touch-based sensing that provides an alternative to traditional mechanical buttons and sliders. Instead of sensing the physical state of a button, capacitive sensing detects the presence or absence of a conductive object near touch screens, touchpads, and proximity sensors. Most often, that object is a part of the human body, such as a finger. In order to understand the evolution of the design process, it is important to understand the basics of capacitive sensing.

Fundamental to any capacitive sensing solution are groups of conductors that interact with their surrounding electric fields. The human body itself is full of conductive electrolytes, covered by a poor dielectric: skin. The fact that our bodies, or more specifically our fingers, are conductive is what enables capacitive sensing for human interfaces.

If you examine a simple parallel-plate capacitor, you will find two conductors separated by a dielectric layer. The majority of the energy in this capacitor is focused between the two plates; however, some of the energy spills over to the area outside the plates. This spillage creates what is called fringing fields, referring to the overflow electric field lines. A well-designed capacitive sensor function requires controlling the PCB traces to prevent fringing fields spilling over into the active sensing area. As you might guess, a parallel-plate capacitor is not a good choice for our desired sensor pattern.

Figure 1 shows a cross section of a single capacitive-sensing button. Under some overlay material, often thin plastic, there are conductive copper areas and conductive sensors. Whenever two conductive elements are within close proximity to each other, a capacitance is created – noted as CP in this diagram – which is generated by coupling the sensor pad and ground plane. CP is the parasitic capacitance and is typically on the order of 10 pF to 300 pF. The proximity of the sensor and ground planes also creates a fringe electric field that passes through the overlay. Since the tissue of the human body is basically a conductor, placing a finger near fringing electric fields adds conductive surface area to the capacitive system.

Figure 1: Cross-sectional view of a capacitive sensor.

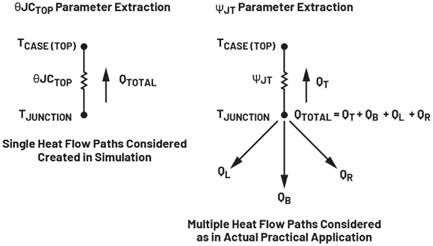

This additional capacitance from the finger – noted in Figure 2 as CF – is on the order of 0.1 pF to 10 pF. Although the presence of a finger induces change, the scale of the change in comparison to the parasitic capacitance is quite small. Capacitive sensing is the process of observing this change.

Let’s call the sensor’s measured capacitance CX;. With no finger present, CX; is equal to CP. When a finger is present, CX; is a combination of CP and CF.

Figure 2: Summation of capacitances.

It is a common misconception about capacitive sensing that a finger needs to have a path to ground for the system to work. This is incorrect. A finger can be sensed because it holds a charge, regardless of whether the finger is floating or grounded.

A typical capacitive sensor is designed on a traditional printed-circuit board, such as a standard FR4 PCB or on a flex-PCB. The sensor uses the same copper already being used for routing signals, so no special materials are required. The sensor’s maximum sensitivity is determined by two main factors: the physical size of the sensor and the combination of the overlay thickness and its dielectric constant. What this means is that a large button with a thin overlay will be more sensitive then a small button with a thicker version of the same overlay.

Calibrating sensors with hardware

A fundamental aspect of any capacitive sensing design is the calibration of the sensor. Calibration prevents the sensor from providing false actives in the system, as well as preventing the sensor from failing when it is supposed to be active. Until recently, individual sensors also had to be accompanied by discrete resistors and capacitors in order to adjust the sensitivity required by each particular sensor.

With this method, engineers had to solder resistors and capacitors to the board, test out the circuit with these values, and then determine if the values were acceptable or if new values were needed. If new values were needed, the process began anew with re-soldering of new resistors and capacitors and testing the system all over again.

In some cases, it might be necessary to use two capacitors in parallel in order to achieve the value needed to obtain the desired key sensitivity balance. Designers also had to take into account the fact that long trace lengths and ground planes add to sensor capacitance, resulting in a poor signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and lowered performance. Adding series resistors and load capacitors could sometimes address this issue.

It is possible to go through this process by building the system on a breadboard and plugging the resistor and capacitors into it. For accurate tuning, this approach probably will not provide enough accuracy since the implementation changes the system, introducing more noise as trace lengths increase and signals travel through additional connectors.

Such manual guess-and-check calibration is very time consuming and quickly erodes the cost-effectiveness of using capacitive sensors. Fortunately, imbalances between sensors on a board can typically be reduced or eliminated by adjusting the discrete capacitors on a per-sensor basis.

Calibrating sensors through firmware

Programmable devices have been gaining popularity over the past few years, enabling firmware-based calibration of sensors as an alternative to the hardware guess-and-check method. The ability to dynamically program calibration enables engineers to adjust the sensitivity of a button by changing values inside the device’s firmware. This approach still entails some guess work but in a much less time-consuming fashion. Parameters can be programmed into the sensor, either by adjusting firmware values and recompiling code for download or by using an adjustable testbench. A process that used to take days can now be completed in hours.

When designing a capacitive sensing application using a programmable IC, the firmware in the application program can scan each sensor, measuring the capacitance. This value, often referred to as the raw count value, is stored in the device. The device also tracks a baseline for the raw counts. The baseline value of each sensor is an average raw count level, computed periodically by the device.

The use of an updated baseline is important for ensuring that a system is able to adapt to drift over time due to temperature and other environmental effects. The current ON/OFF state of the sensor is determined using the raw counts and the baseline delta. This allows the performance of the system to remain constant even though the baseline may drift over time. Figure 3 shows the transfer function between difference counts and button states that is implemented in firmware.

The hysteresis in this transfer function provides clean transitions between ON and OFF states even though the counts are noisy. This provides a de-bounce function for the sensors. The lower threshold is called the Noise Threshold, and the upper threshold is called the Finger Threshold. Setting the threshold levels determines the overall performance of the system and can affect the tolerance of the system for false actives and sensing failures. With very thick overlays, the signal-to-noise ratio is low. Setting the threshold levels in this kind of system can be challenging.

Pre-defined firmware development tools can facilitate the design of capacitive sensors by providing device interconnects, I/O drive modes, and APIs for both capacitive sensor operation and calibration. Reference code provides a starting point for basic functionality and also serves as a learning tool, resulting in easier customization and optimization for a particular project.

Figure 3: Transfer function between difference counts and button states.

Developers can use standard debugging tools instrumented to reduce the guess-and-check work of calibration by providing visual feedback in real-time. By connecting a project board to a PC, the results of testing can be monitored in real-time and can be used to make any required adjustments automatically, homing in on the optimal calibration parameters. Such calibration tools accelerate development by providing real-time feedback for capacitive sensors.

Calibrating sensors through software

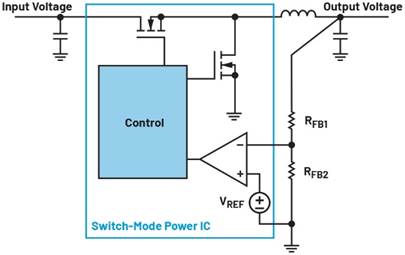

Recently, software has become a feasible way to calibrate capacitive sensors. These programs integrate the math behind the sensing method, essentially hiding it from the developer. The tools provide high- and low-level application programming interfaces (APIs). These APIs work together with the data being collected and stored in the IC, removing several steps when compared to sensor calibration through firmware. Some APIs enable scanning the sensors, setting the resolution, setting clock signals and timing, controlling logical outputs, and even sleeping or waking the device.

These software tools control what otherwise would have been written in a main.c file (or its equivalent), reducing the amount of code that needs to be written. This simplifies the process by taking away control. For example, the ability to control when the device scans sensors directly is relinquished, as well as the ability to call a function to put the device in sleep mode since the software handles that function. In return, you gain a visual interface that allows you to watch the status of your sensors. It is with this interface that you can change the calibration and watch the results in real-time. While you watch, the software takes care of all the APIs in the background. It wakes up the device, scans the sensors, and puts the device back to sleep. It also takes care of waking the device up again after the proper interval (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Calibrating a sensor using Cypress' CapSense® Express Tool.

Visual software design tools will continue to help usher in this new era of capacitive sensing input devices. OEMs will benefit from the cost savings resulting from using fewer components, as well as higher reliability and longer product lifetime. New development tools now make it just as fast, or even faster, to implement a capacitive sensing input system than older mechanical systems.