Choosing parallel versus serial flash has traditionally meant gaining speed at the cost of complexity. This no longer needs to be the case.

The SPI Flash Interface (SPIFI), a patent-pending feature initially available on NXP’s latest ARM Cortex-M3 microcontrollers, lets designers of 32-bit embedded systems use a small, inexpensive serial flash in place of a larger, more expensive parallel flash. With SPIFI (“spiffy”), the external serial flash appears in the microcontroller’s memory map and can be read like other on-chip memory. This essentially eliminates the traditional tradeoff associated with choosing the type of external flash to be used in an embedded system, and gives designers a new way to minimize size and cost while delivering the required system performance.

NXP has developed a peripheral function, initially available on its new ARM-based LPC1800 Cortex-M3 microcontrollers, that lets designers of embedded systems use external serial flash memory in place of larger, more expensive parallel flash. The patent-pending peripheral, called the SPI Flash Interface (SPIFI), lets external serial flash memory appear in the microcontroller’s memory map, so it can be read like an on-chip memory. This gives designers a new way to meet performance demands while creating a system that is easier to configure, uses smaller packages, requires less board space, and is less expensive to build.

The need for external flash

Embedded applications that use a 32-bit microcontroller (MCU) are increasingly tasked with offering a range of sophisticated features for managing multimedia, photos, and other data-intensive content. This is particularly true of systems that present a human interface, since today’s users have come to expect a graphical display that lets them interact with window boxes, photos, animations, sound files, and more. As products become increasingly international, they have to operate in different languages and may need to support several sets of alphabets and non-Roman characters. All these requirements place extra demands on the system’s memory resources.

Most 32-bit microcontrollers are equipped with on-chip flash memory that can be used to support data-intensive features, but it’s often not enough to support the entire application. The on-chip flash is typically limited to 1 Megabyte or less. That may be enough to house the bulk of the critical application code, but it may fall short when it comes to storing all the other things the application needs, such as look-up tables, images, photos, sound files, multiple languages, and so on. For these items, designers often turn to external flash memory.

External flash memory is significantly cheaper than on-chip flash and is readily available in sizes in excess of 8 Megabytes. Flash memory can also add an extra level of flexibility to the system, since it can be used to patch or upgrade software once the system is in the field.

The parallel/serial tradeoff

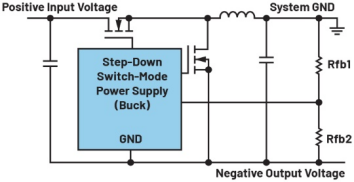

When choosing what kind of external flash to use, parallel or serial, designers have traditionally had to balance several tradeoffs. Parallel flash is often faster than serial flash, but requires more pins, more PCB traces, and more board space.

Figure 1 shows data transfer rates for typical parallel and serial flash devices. For the parallel flash, the graph assumes a fixed access time of roughly 90 ns without buffering. With these conditions the maximum transfer rate for a 16-bit-wide parallel flash is 22 Mbytes/sec. For the serial flash the maximum clock frequency is 80 MHz giving a per-bit transfer rate of 80 Mbits/sec. For a quad device this means a maximum transfer rate of 40 Mbytes/second. This calculation ignores any control bits but quad SPI devices support bursting which is used by the SPIFI interface This allows the SPIFI interface to approach these transfer rates.

Figure 1: Typical transfer rates of serial and parallel flash memories.

Interface

Mode

Access Time (nS)

Effective Throughput (MB/S)

Parallel

8 Bits

90

11

16 Bits

90

22

Serial

Single

12.5*

10

Dual

12.5*

20

Quad

12.5*

40

Table 1: Parallel versus Serial Flash Performance.

*Effective access time.

As shown in Figure 1, a typical 16-bit parallel flash memory delivers a data transfer rate of 20 Megabytes per second. In systems that use a 32-bit microcontroller with a 32-bit bus for the external memory (like those from NXP), the designer can opt to use two 16-bit parallel devices in combination for a rate of 40 Megabytes per second. However, the added speed comes at a cost. The configuration uses two separate parallel flash memories, each housed in a package with dozens of pins, and that may be more, in terms of package size, pin count, and PCB space, than the designer can afford.

Serial flash, which typically uses the simple four-pin Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI), can be a good alternative to parallel flash when space, power, and cost are concerns, but it’s much slower. Figure 1 shows that a typical SPI flash operating at 50 MHz transfers data at roughly 5 Megabytes per second (eight times slower than a configuration that uses two 16-bit parallel devices). Another consideration is that the SPI interface on most microcontrollers is connected to the MCU’s peripheral matrix, where data has to be received by driver code and put into on-board RAM before the processor can access it. This can slow things down, since each read from serial flash has to go through an SPI software layer. Depending on the application, using the standard SPI interface for external memory may not be fast enough.

The new Quad SPI flash format, which uses a modified, six-pin SPI configuration, is much faster than traditional SPI formats. As shown in Figure 1, Quad SPI delivers a transfer rate of 40 Megabytes per second, which is the same as using two 16-bit parallel devices. Using Quad SPI is often much less expensive than the parallel approach, since it uses far fewer pins and a much smaller package. It would seem that Quad SPI flash would be a good replacement for parallel flash in embedded systems, but the reality is that today’s 32-bit microcontrollers aren’t designed to support Quad SPI flash at its maximum speeds. This is because the Quad SPI interface, like the traditional SPI interface, is connected to the microcontroller’s peripheral matrix.

Eliminating the tradeoff

NXP has developed a new peripheral function, called the SPI Flash Interface (SPIFI) that essentially eliminates the parallel/serial tradeoff. The patent-pending SPIFI (“spiffy”) peripheral lets low-cost SPI and new Quad SPI flash memories appear in the memory map of an ARM Cortex-M3 microcontroller, so the MCU can use external SPI flash with only a minimal performance penalty compared to external parallel flash memories. The complete memory space of the external SPI flash appears in the MCU’s memory map, so the microcontroller can access the external memory directly, without a software API or library.

When used with a Quad SPI flash, for example, the SPIFI peripheral supports a data transfer rate of up to 40 Megabytes per second. The designer can choose a less expensive SPI flash device, with its compact footprint and simple configuration, but doesn’t have to sacrifice performance. The designer may also be able to choose a smaller, less costly microcontroller, because the system won’t need a bulky interface for external parallel memory. The SPIFI peripheral enables an embedded system that makes better use of memory resources yet remains compact and efficient while lowering overall cost.

The SPIFI peripheral is a dedicated function that will initially be available on the NXP LPC1800 series of ARM Cortex-M3 microcontrollers. It will also be available on upcoming product lines, including the low-cost Cortex-M0 series and the Cortex M4 line of digital serial controllers (DSCs).

SPIFI supports most serial flash devices on the market today (including those with quad read/write capability) and is designed for easy configuration and programming. It uses four or six pins (depending on the type of serial flash used), works with a small register set, is optimized for efficient memory transactions, and uses software commands that reduce CPU overhead and streamline memory interactions.

How SPIFI works

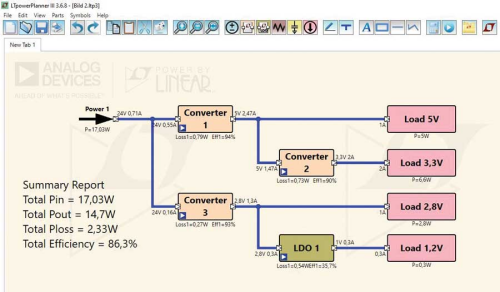

Figure 2 shows a block diagram of the SPIFI peripheral. The SPIFI function is connected to the microcontroller’s Application High-speed Bus (AHB) matrix, which is used for the processor core and the on-chip memories. The SPIFI peripheral presents the contents of the external SPI flash in the microcontroller’s memory map. Once the boot code in the on-chip ROM initializes the SPIFI interface, the external SPI memory looks just like an on-chip memory to the core processing unit.

Figure 2: Block diagram of the SPIFI peripheral.

Initialization sequence

All of the drivers required for the SPIFI interface are available in ROM. For reading, only one call to a routine is made to initialize the SPIFI peripheral. After the initialization sequence, the entire SPI flash content is accessible as normal memory using byte, half word, and word accesses by the processor and/or the DMA channels. Erasure and programming are handled by a simple API call, which accesses commands in ROM, so using the external SPI memory is as easy as using on-chip flash memory.

Booting from SPIFI

For systems that need the microcontroller to boot from external serial flash, the NXP LPC1800 microcontroller has been equipped with a mechanism that includes SPIFI as a boot source. There are two ways to select the boot source. The first uses the microcontroller pins to determine which interface to boot from, and the second relies on the user to program a non-volatile location to choose the interface. Using the non-volatile location saves the pins from having dual-use functions.

Physical interface

Figure 3 shows the physical interface of the SPIFI peripheral. It uses the standard four pins for traditional SPI devices; when configured with Quad SPI memory it uses an additional two pins to support the quad capability.

Figure 3: Physical interface of the SPIFI peripheral.

Different serial flash vendors and devices accept or require different commands and command formats. The SPIFI peripheral provides sufficient flexibility to be compatible with most common SPI flash and includes extensions to help insure compatibility with future devices.

Reduced register set

A compact register set gives the SPIFI peripheral a considerable amount of intelligence while keeping it simple to use. It takes just eight registers to control the SPIFI function, interface with the external SPI memory, store and retrieve data, and monitor operation. Since the built-in ROM API governs setup, programming, and erasure, handling the external SPI memory in an application is a matter of a few calls. As a result, the SPIFI peripheral is simple to configure and easy to support in the application.

Software commands

The external memory responds to commands sent by the microcontroller software and to commands automatically sent by the SPIFI peripheral when its software reads the serial flash region of the memory map. Commands are divided into fields called opcode, address, intermediate, and data. The address, intermediate, and data fields are optional depending on the opcode. Some memory devices include a mode in which the opcode can be implied in Read commands for higher performance. Data fields are further divided into input and output data fields depending on the opcode. All commands to the external SPI memory can be handled by calls to the ROM API. The SPIFI ROM API driver lets the contents of the external SPI memory be accessed using simple load commands, so the application code remains compact and easy to write.

CPU-independent operation

The SPIFI software can read data from the external memory and write it to RAM or a peripheral without involving the CPU. With microcontrollers that have an integrated LCD controller, for example, this feature can be used to enhance performance and save power. Images can be stored in the external memory and fetched by the LCD controller. Since the LCD controller reads most of its data from sequential addresses, the SPIFI peripheral can pre-fetch the addresses so they’re ready when needed, with essentially no wait states. The entire operation can happen without getting the CPU involved, and there’s no need to load the images into on-chip RAM before the LCD controller fetches them. That means the system can use a microcontroller with less on-chip RAM, or can free up its existing RAM for other tasks. Also, since the images are fetched directly by the LCD controller, the LCD display can refresh graphics faster, so simple operations like opening and closing windows appear smoother. Also, to save power, the system can use a slower clock speed without having a noticeable impact on the display’s performance.

Direct execution

From a software point of view, the microcontroller can execute code directly from the external SPI memory. Direct execution can be helpful when using in-field upgrades or when replacing functions originally shipped in on-chip flash. Validated upgrade code can be placed in the external flash. If, for example, the system’s function addresses are in a table stored in on-chip flash, the table can be reprogrammed with the address of the routine now housed in external flash. Alternatively, if the page containing the start of the original routine is stored in on-chip flash, the page can be updated with a branch long jump to the new routine in external flash. In either case, the new code doesn’t need to be loaded into the on-chip RAM to execute, because the SPIFI peripheral allows direct execution from the external memory.

Executing code from an external memory is never as fast as using on-chip memory. The SPIFI peripheral isn’t intended for use with real-time functions that require peak performance but, for less critical code sequences, SPIFI can be a very attractive option.

Write-while-execute functions

The SPIFI supports write-while-execute functionality, which means it can program or erase the external memory simply and quickly, even when the processor is executing code from on-chip flash. Since the SPIFI peripheral can run on its own, without interaction from the CPU, the system can perform its functions without interruption while the serial flash is being reprogrammed.

This feature can be used to perform software upgrades in the field, because the system can write to the external memory without interrupting critical application code. In a smart meter, for example, the metering function needs to operate continuously, even during a software upgrade. With SPIFI, the utility company can configure the system to write any new code to external flash, without interrupting the active metering function, and can then integrate the new code into the system. Similarly, in a system that has a USB port, new code can be placed on a portable USB drive and transferred to the external flash without interrupting critical operations.

Conclusions

NXP’s new SPI Flash Interface (SPIFI), a patent-pending feature initially available on its new ARM-based LPC1800 Cortex-M3 microcontrollers, lets external serial flash memory appear in the microcontroller’s memory map, so it can be read like on-chip memory. This gives designers access to a large amount of external flash memory while reducing system costs and minimizing the design footprint.

The SPIFI peripheral creates a way for designers to use a small, inexpensive serial flash where they might previously have needed to use a larger, more expensive parallel flash to meet the system’s performance requirements. Designers can take advantage of the many benefits of serial flash — low-cost, small size, simple configuration — without making large sacrifices in performance. SPIFI also lets designers opt for a microcontroller without a parallel interface, for a smaller, less expensive design that still delivers the required performance.

The NXP roadmap for SPIFI includes migration to other Cortex-M families, including the low-cost Cortex-M0 series and the upcoming Cortex-M4 series of Digital Signal Controllers.