A wide range of sleep modes enables applications to idle at power levels so low they are hard to measure.

Historically, microcontroller vendor competition was largely dominated by a "faster is better" philosophy. Having finally hit the power wall — in spite of the combined efforts of Moore's Law and Ohm's Law — semiconductor manufacturers are now competing to see who can make the lowest power MCUs. "Low power" has now been replaced by "ultra-low-power." When it comes to low power, the race to the bottom is heating up.

Embedded developers currently have a wide range of very capable low-power MCUs from which to choose. It is an embarrassment of riches, compounded by conflicting (if carefully qualified) claims that MCUs have the lowest active, standby, sleep, deep sleep, or other operating characteristics. In fact, the proliferation of process technologies, power management techniques, and operating modes has made it difficult to do an apples to apples comparison between different MCUs just by looking at their data sheets.

Embedded developers are increasingly utilizing evaluation and development boards to test their application code on different MCU platforms. This article will take a hands-on look at Microchip's XLP 16-bit Development Board (see Figure 1), which is designed to showcase the numerous software-selectable, low-power operating modes for its nanoWatt XLP eXtreme Low Power MCUs — in this case the 16-bit PIC24F16KA102. The board and its demonstration program — accompanied by well commented C source code — makes it easy to explore both the parameters and the trade-offs involved in utilizing various power-down modes.

Powering down

Active or dynamic power is largely the power required to switch logic gates. As processors have become more complex, moving to smaller process geometries has continually reduced core voltages, with the resulting power savings far outweighing the added current load of the extra transistors. Thanks to Ohm's Law, core voltage (VDDCORE) has a dramatic impact on both active and static power. Still, with Moore's Law now running headlong into some laws of physics, that free ride is coming to an end.

Figure 1: Microchip's 16-bit XLP Development Board (Source: Microchip. Used with permission).

Active power also correlates directly with clock speed, so most MCUs will automatically dial back the system and/or secondary clocks whenever the application allows it. Dynamic voltage and frequency scaling — once the domain of PMICs — are increasingly common in higher-end MCUs. Combine that with multiple fine-grain voltage islands, numerous power-down states with quick recovery times, and so-called smart peripherals, and it becomes difficult to see how much more MCU designers can do to reduce active power.

Static power is another matter, and that is where the greatest gains are being made. Static power is what you are left with when the system clock is turned off. It's largely dependent on process technologies and device design to control transistor leakage, which also varies with voltage and temperature. Within those design limitations, MCUs that can reduce VDDCORE as far and as often as possible will have the greatest impact on both static and dynamic power. That is basically what Microchip's "nanoWatt Technology" is all about.

NanoWatt sleep modes

Microchip introduced its nanoWatt Technology for PIC MCUs back in 2003. It was not a new technology so much as a series of process, design, and software-controlled power saving features which enable these MCUs to deliver "overall power consumption in the nanoWatt range while in Sleep mode," according to the data sheet. New power saving features included an idle mode, an on-chip, high-speed oscillator with PLL and programmable prescaler, a watchdog timer (WDT) with an extended time-out interval, ultra-low-power wakeup (ULPWU), low-power options for the system and secondary oscillators, and a low-power, software-controlled brown-out reset (BOR).

Raising (or lowering) the bar, Microchip's more recent nanoWatt XLP Technology defines this specification as any MCU below:

- 100 nA for power-down current (IPD)

- 800 nA for watchdog timer current (IWDT)

- 800 nA for real-time clock and calendar (IRTCC)

The key to XLP is the use of several software-selectable hardware configurations which enable an application to dynamically change power consumption during execution. Instead of your compiler making these decisions, your application can make them at runtime. Table 1 details what happens during the various operating modes.

Operating Mode

Active Clocks

Active Peripherals

Wake-up Sources

Typical Current

Typical Usage

Deep Sleep (1)

- Timer1/SOSC

- INTRC/LPRC

- RTCC

- DSWDT

- DSBOR

- INT0

- RTCC

- DSWDT

- DSBOR

- INT0

- MCLR

< 5 Na

- Long life, battery-based applications

- Applications with increased Sleep times

Sleep

- Timer1/SOSC

- INTRC/LPRC

- A/D RC

- RTCC

- WDT

- ADC

- Comparators

- CVREF

- INTx

- Timer1

- HLVD

- BOR

All device wake-up sources (see device data sheet)

50-100 nA

Most low-power applications

Idle

- Timer1/SOSC

- INTRC/LPRC

- A/D RC

All Peripherals

All device wake-up sources (see device data sheet)

25% of Run Current

Any time the device is waiting for an event to occur (e.g., external or peripheral interrupts)

Doze(2)

All Clocks

All Peripherals

Software or interrupt wake-up

35-75% of Run Current

Applications with high-speed peripherals, but requiring low CPU use

Run

All Clocks

All Peripherals

N/A

See device data sheet

Normal operation

Note: 1: Available on PIC18 and PIC24 with nanoWatt XLP™ Technology only.

2: Available on PIC24, dsPIC and PIC32 devices only.

Run, Idle, and Doze modes should be pretty clear from Table 1. However, take a brief look at the Sleep Modes before we do a reality check using the XLP Development Board.

- Sleep Mode — This is the basic low-power mode for all PIC MCUs. Here the system clock and most peripheral clocks are shut down, with state retention for the program counter (PC), SFRs, and anything in RAM. Wake up can be initiated by the WDT, the secondary clock, or various external interrupt sources. Wake up times vary but are usually in the low microseconds.

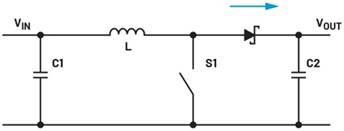

- Deep Sleep — In Deep Sleep mode, the MCU core, most peripherals, on-chip voltage regulators, and (sometimes) RAM are powered down. While Deep Sleep is the lowest power state, waking up from it is non-trivial (see Figure 2), requiring a device reset rather than the smooth transition back from Sleep Mode. However, in going into Deep Sleep mode all I/O states, the secondary clock and RTCC are maintained so that the rest of the system can continue operating. Upon reset the program resumes execution from the reset vector once the application reconfigures the peripherals and I/O registers.

Because of the overhead (read:time) required to implement Deep Sleep Mode, embedded developers need to consider when to utilize it. Microchip recommends using it when your application can support sleep times of one second or longer, when it doesn't require access to any peripherals while asleep, when it still needs accurate, low-power timekeeping, and when it's operating in environments that may experience extreme temperatures.

Deep Sleep makes a lot of sense for low-power wireless sensor nodes that may need to operate for years from a coin cell battery and only wake up every few seconds to transmit data for a few microseconds. It also makes sense in energy scavenging applications, an option for the XLP board but not one I will to review here. In less extreme applications, standard Sleep Mode is recommended.

Figure 2: Procedure for waking up from Deep Sleep Mode (Source: Microchip. Used with permission).

XLP – the demo

Microchip chose to build its XLP Development Board around the PIC24F16KA102 in order to demonstrate that chip's low-power capabilities, which are broken out in Table 2. Without going too far into the data sheet details, the chip features a 16-bit, 16 MIPS core running at 1.8 to 3.6 V, 16 kbytes of flash, 16 kbytes of SRAM, 1.5 kbytes of DRAM, 512 bytes of data EEPROM, a 10-bit ADC, two UARTs, and a charge time measurement unit (CTMU) enabling nine channels of capacitive touch (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: PIC24F16 family block diagram (Source: Microchip. Used with permission).

Deep Sleep (nA)

20

Sleep (nA)

25

WDT (nA)

420

32-kHz Oscillator/RTCC (nA)

520

I/O port leakage (nA)

±50

1 MHz Run (μA)

195

Minimum VDD

1.8

Table 2: PIC24F16KA102 power specifications.

The board itself looks to be plug-and-play, since you only need to plug in a USB cable to power it and watch the sample program run that is already embedded in the MCU. In practice, there are a lot of moving parts to download, configure, and figure out before you can begin.

Getting started

The kit itself contains the board, a mini-B USB cable, and a brief information sheet. The board itself can run from two AAA batteries, a CR2032 coin cell, a Cymbet CBC-EVAL-08 energy scavenging demo board, a USB cable, or an external 9 V power supply — none of which are supplied. I chose to power it from the USB cable.

First you need to download and install the XLP 16-bit Development Board code (currently v1.2) from Microchip's web site. The software only claims to run on Windows XP and Vista, but it installed easily on my 64-bit Windows 7 machine, though as a 32-bit program. The board comes with a demo program already installed in flash, so you only need to run a terminal emulation program on your PC to observe it in operation — which proved to be a lot more easily said than done.

Windows XP and Vista come with HyperTerminal, which cannot support the high data speed required by the XLP board — an amazing 1 Mbyte/second. A Microchip engineer explained that speed is necessary for fast data exchange with the Cymbet energy harvesting board, whose tiny thin-film batteries need to push out data quickly before they fade out. The XLP software download includes the open source program RealTerm, which installs along with the demo program source code and documentation.

After a smooth install, I connected the board, turned on RealTerm — and couldn't get it to work. After reading lots of release notes, checking ports with Device Manager, and changing parameters, I finally found a directory called USB Serial Emulator, a subdirectory called "drivers", and finally USBDriverInstaller.exe. Running that program solved the problem (see Figure 4). It still eludes me why you need this driver when there is a Microchip MCP2200 USB-to-UART serial converter sitting right next to the USB jack.

Figure 4: RealTerm running the XLP demo program.

The XLP board incorporates sensors for temperature, voltage, and touch, all of which you can switch in or out using jumpers, or you can poll or ignore them using software. Pressing S3 for more than two seconds toggles the MCU between Sleep, Deep Sleep, and Idle Modes; pressing it briefly disconnects the UART so you can measure the system power with it out of action. Pressing S2 cycles between the temperature sensor, voltage sensor, and capacitive touch pads, with the results from all three measurements being shown instantly. S1 (MCLR Reset) can wake the MCU from Deep Sleep Mode, as can S2 (INT0) and the RTCC, which wakes the MCU every 10 seconds in the demo program.

Measuring nanoamps

Not that I do not trust Microchip, but both the fun and much of the point of doing a review involves checking out their claims that this is an ultra-low-power chip. Up until now I had been proud of my B&K 2831E DMM, with its maximum resolution of 0.1 μA (aka 100 nA); however, it clearly wasn't up to the task. Since Microchip is in Phoenix and National Instruments (NI) is practically next door to me in Austin, Texas I called a friendly engineer at NI and dragged the kit over to hook it up to their expensive gear (see Figure 5).

Despite what the datasheet and the user guide led me to expect, we couldn't get the board to consume less than 500 nA under any circumstances (after allowing for offsets and noise). Since that is what the chip is supposed to consume with the RTCC running, the clock was the obvious suspect. But how to turn it off?

A call to a Microchip engineer confirmed that the RTCC does indeed stay on unless you turn it off, which you can only do by commenting out InitRTCC() in main.c. Time for some reprogramming.

Figure 5: The XLP board gets put to the test.

Programming for nanoamps

To do more with the XLP board than make the lights blink and conduct measurements, you need to reprogram it. You need to download and install Microchip's MPLAB IDE and one or more compilers. I chose version 8.60 of MPLAB IDE (which includes the MPLAB C compiler for PIC24 MCUs and HI-TECHs) instead of the newly announced MPLAB X, which was still in beta at the time. All three installed easily, along with a number of other guides, tools, and libraries. I ordered Microchip's PICkit 3 in-circuit debugger/programmer and a current measurement cable (for JP9), both of which arrived overnight from Digi-Key.

Figure 6: XLP demo program recompiled and ready to run.

Firing up MPLAB, I selected Project/Open, went to directory…/XLP 16-bit Development Board/source, and clicked on XLP16Demo.mcp. Next, I had to select a compiler from Project/Select Language Toolsuite. I chose the Microchip C30 Toolsuite, which includes the compiler, debugger, linker, assembler, and archiver. There are a lot of other tool options, none of which work until you install them except for the HI-TECH tools, which were also installed along with MPLAB.

Next, I selected Project/Build All (Ctrl-F10) and everything went like clockwork (see Figure 6) – no need to debug just yet. We need to test this program on the board before we start messing with it.

Programmer/Select Programmer/PICkit3 did the job. Microchip warns you not to hot swap the PICkit, so I plugged it into the board and then connected a USB cable to it. MPLAB ran some tests on the programmer, was satisfied, and announced "PICkit3 connected." Well maybe not — moments later I got "PK3E0045: You must connect to a target device to use PICkit3."

I connected another USB cable to the board, which powered it up. MPLAB detected the board but I had to choose the target device. Choosing the PIC24F16KA102 from a long list of supported chips, I got "Target detected" along with a device number. So far, so good. Next "Programmer/Program" quickly led to "Programming/Verify complete." Starting up RealTerm again, the program ran as advertised (see Figure 4). Time to mess with it.

Taking Microchip's advice, I opened main.c, searched out InitRTCC() and commented it out. I rebuilt the program, downloaded it onto the PIC and ran it, watching it perform on the PC. I also hooked up the ammeter on my DMM to the current measurement test point (JP9). Where previously it had at least shown signs of life, now I only got a string of zeros. Time for the acid test using much better test equipment.

The acid test

I revisited my friends at NI, who again hooked the board up to their PXI-4132 Precision Source Measurement Unit (SMU), a $3,500 instrument capable of a 10 pA measurement resolution. I fired up the demo program (with RTCC now disabled) and pressed S2 (MCLR), which promptly shot 300 nA through their device that was calibrated for no more than 100 nA. If it were an analog meter the pointer would have been bent. I promised not to do that again.

After repeated (and forewarned) button pushing, the lowest current we could measure was just under 50 nA, double what the spec sheet claimed (20 nA in Deep Sleep, 25 nA in Sleep). What was that about?

As we pored over the datasheet, NI's guess was that Microchip would have specified the chip at 1.8 V — its lowest VDD — and not the 3.32 VDD that we measured. A quick email to Microchip confirmed our suspicions: "You are correct. The 20 nA number you mentioned before is the 1.8 V spec. At 3.3 V our typical specs are 100 nA for Sleep and around 40 nA for Deep Sleep." Our own measurements were slightly higher but pretty close to the mark.

But wait, there's more

Actually there isn't, at least not in this review. However, the XLP board includes three capacitive sense buttons which you can program for a variety of functions. Its PICtail connector (J7) accepts a number of daughter cards, including ZigBee and MiWi RF boards. It has a connector (J8) that accepts a Cymbet energy scavenging board with a built-in solar panel. Software and firmware support for energy harvesting come with the XLP board, including a full energy harvesting demo with source code. When packaged together it's known as the XLP 16-bit Energy Harvesting Development Kit. We'll reserve that for a future review.

In short, the XLP 16-bit Development Board is an inexpensive ($60), highly extensible platform for developing ultra-low-power applications.

Sources

1. Microchip XLP 16-bit Development Board.